By Paul H Williams

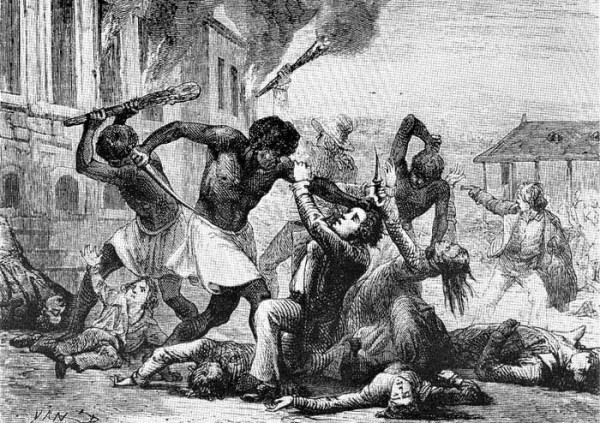

From the very moment some Africans were captured to be sold into servitude in the Caribbean they were planning their escape. They were skilled and cunning warriors, tribal leaders with a zest for freedom. They had absolutely no intention of submitting themselves to their enslavers.

Thus, it was no wonder many of them abandoned the plantation, fled into the interiors of Jamaica, creating headaches and embarrassment for the British militia whose pursuits were unyielding. It was their flight to the mountains that perhaps earned them the moniker, Maroon.

Several explanations for the name are proffered, but the one that says it is derived from the Spanish word, cimaron, which means summit or mountain, is quite plausible. Another source says the Spanish word, cimarron, means “wild” and “savage”. And then, there is the French, negre marron, “escaped Negro”.

The rough and rugged terrains of the interiors of the island to which they fled were ideal for the guerilla warfare that the Maroons waged against the British. Their knowledge of the geography of the regions were unmatched by the British, many of whom died in the unbearable conditions in the hills.

The dense vegetation, streams, rivers, waterfalls, caves, and underground paths were used to confuse and frustrate the British. In the west, the almost impenetrable Cockpit Country, a series of steep cliffs and hillocks covered with trees and undergrowth, was their haunt and refuge.

They could appear and disappear at random, frightening and haunting the British, experts at camouflage they were. And, at night, their raids on outlying plantations provide them with food, weapons and ammunitions. Yet, they did not need the food of the British to survive. They made use of the fruits and provisions of the land, and the abundance of marine and river creatures.

Add to all of that, their indomitable spirit, which wore down the resolve of the British, who, tired, weary and defeated, offered treaties of peace and friendship. The first treaty was signed with the Leeward Maroons of the Cockpit Country. Colonel Guthrie and Captain Saddler represented the British, while the Maroons were represented by their leader Captain Cudjoe, Captain Johnny and Captain Cuffee.

They met in an opening, surrounded by concealed Maroons. Captain Cudjoe was cautious at first. He did not trust the British and took his time in appearing. He was from the fierce Ashanti people of Africa’s Gold Coast, and was as brave as he was cunning. Surrounded by the British, who were in turn surrounded by the guerilla fighters, he signed the treaty, which was subsequently ratified by King George II, on March 1, 1738.

Among other things the Maroons were given 2500 acres of tax-free land, to be theirs forever. They got sovereignty of the land, meaning the British police and military had no authority within those acres, and they were also reserved the right to choose their leaders.

A little over a year after the Leeward Maroons signed the treaty with the British, the British ended their protracted efforts to rein in the Windward Maroons. The war ended after Captain Quao unleashed terror upon the British with his ambush tactics. In the final battle, the British soldiers and militia, led by Lieutenant George Concannon and Lieutenant Thickness were outfoxed and were left in shambles as the war climaxed in the Spanish River valley.

Three months after their defeat, the British, led by Captain Adair, set out to find Captain Quao to make peace. But, before they reached, Quao had captured a British soldier called the Laird of Leharret, who informed him that Cudjoe had made peace with the British, and that Quao should do likewise.

Quao was convinced, but he had to seek counsel from Nanny, the feared matriarch of the village. Nanny was furious. Signing the treaty would be a sign of weakness, she argued. Moreover, the Laird of Laharret had violated her space and should be killed. The Laird was subsequently executed.

Captain Adair and his men, guided by a captured Maroon, walked over precipices, steep slopes and inclines to reach Quao’s village. The captured Maroon announced their presence, which Quao already knew. It took a while for the two sides to come face to face. Being persuaded that the British were serious about the treaty Quao acquiesced.

However, tension brewed between Adair and Colonel Robert Bennett, who also pursued the Maroons. When Bennett heard of the proposed treaty, being of superior rank to Adair, he insisted that it be signed in his name. A quarrel ensured between the regular officers of Adair’s command, and Bennett’s militia officers.

Bennett eventually backed down, and the treaty was concluded by Adair and Quao on June 23, 1739. Yet, in the official records it was signed by Bennett, who apparently took the matter further after peace was achieved.

Nanny refused to sign the treaty. However, she and her people were given 500 acres of land by Governor Edward Trelawny. The land was surveyed by Thomas Newland and patented on April 20, 1741 by John Udey, clerk of patents.

From this, the question of where the Windward Maroons should have settled caused a rift between Nanny and Quao, and their followers. Quao took his to a place called Crawford Town, while Nanny and hers went to the land given them. It is now known as Moore Town, one Jamaica’s five major Maroon villages.

The Maroons Part II – evolution and legacy

‘All Ah We A One’; Jamaican Diaspora or home on the Rock