If Columbus’ so–called ‘discovery’ of Jamaica was a “buck-up” as Jamaicans would say, the English capture and subsequent colonization of the island could be described in the words of another Jamaican saying ‘if you cant catch Quaco, you catch him shut’, meaning if you cant get what you really want, try and get something so you don’t go empty-handed. In this context, the capture of Jamaica from the Spaniards was like a consolation prize as the island was never a particular target for English attention or capture because of its lack of wealth and limited strategic importance in the 17th century rivalry among the European powers.

Jamaica was in fact captured from the Spanish by nothing more than an expeditionary force whose original target was the wresting of Hispaniola from Spain. The forces had been sent by Oliver Cromwell as part of his Western Design to break Spain’s stranglehold on the New World. When its main objective of the capture of Hispaniola failed, the remnants of the forces sailed on to nearby Jamaica which was known to be sparsely populated and poorly defended and captured the island with virtually no resistance from the Spaniards. On May 10 1655, led by two Generals – Penn in charge of the fleet and Venables the commander on land, the expeditionary forces landed at Passage Fort in Kingston harbour. The Spaniards capitulated after waiting for one week for the English attack on Spanish Town which never came but during this time they took the opportunity to hide their valuables, freed and armed their enslaved Africans and left them behind to harass the English invaders. These freed enslaved Africans and their descendants were later to win fame as the Maroons.

The Maroons Part I: A story of Freedom and Defiance – Read Now

By the terms of their capitulation, every Spanish man, woman and child had to leave the island with only what they could carry, departing over Mount Diablo and Moneague to the north coast and on to Cuba. From all contemporary accounts they went weeping. The Spanish later mounted stout but unsuccessful attempts under the leadership of its Governor Christobal Arnaldo de Ysassi to recapture the island. The decisive battle was fought in May 1658 when the Spaniards landed at Rio Nuevo and after a bloody engagement the invaders were routed by the English led by Col. Edward D’ Oyley. In 1660 Ysassi and the remnants of his army escaped to Cuba bringing Spanish influence in Jamaica to an end. Ten Years later, the island was formally ceded to England under the Treaty of Madrid.

The final attempt to snatch Jamaica from the British took place at the end of the 17th century when a large French force under Admiral Jean du Casse landed on the eastern side of the island and ravaged the countryside. However, when they landed at Carlisle Bay in Clarendon and attempted a second assault they were soundly repelled in a bloody battle that resulted in 700 deaths. The way was now clear for sustained colonization of the island which the English proceeded to do for the next 300 years.

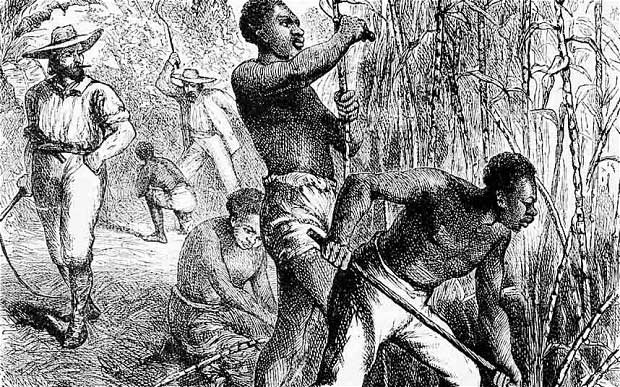

The first English settlers concerned themselves with growing tropical crops which could easily be sold in Europe and North America, including tobacco, indigo and cocoa before turning their attention to sugar, the most profitable crop of all. Once established, the industry grew prodigiously. In 1673 for example, there were only 57 sugar estates in the island but by 1739, the number had grown to over 400 estates. For the next century and a half the history of Jamaica was essentially the story of Sugar and Slavery. It is the story of how, through the enormous wealth created by sugar, Jamaica became the finest jewel in the English crown. It is also the story of how in order to create that wealth, the English planter required a source of large cheap labour, out of which the trade in African enslaved persons grew and slavery established as the basis of the economic and social order of the society.The society created by slavery was rigid, base, greedy and inhuman consuming life, energy and thought and fertilized the Industrial Revolution of England with the profits from its labour.

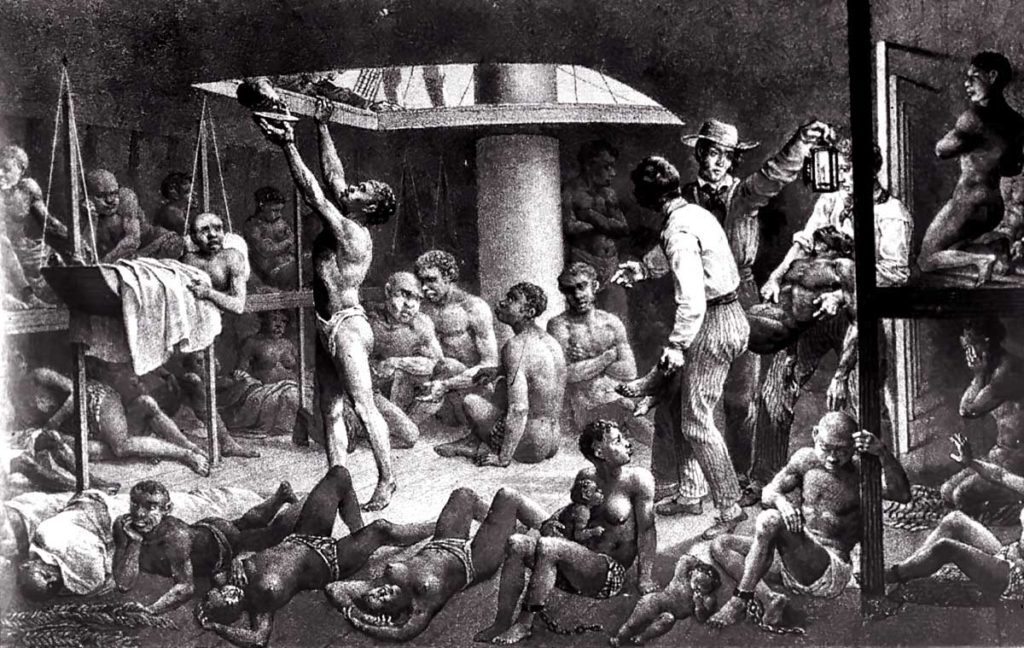

The first great influx of Africans arrived in Jamaica between 1693 and 1694. By 1734, the African population had risen to 87 thousand while the whites numbered under 10,000. By 1807 when the trade in Africans became illegal, over xxxxx Africans were forcibly captured and shipped to labour on the sugar estates of Jamaica. What was so despicable about the trade in Africans and slavery itself was the fact that to the white English planters, the Africans were not seen as humans but as chattel to be owned, used and disposed of like any other piece of property. From the forced capture of men, women and children from their villages in Africa to the horrors of the Middle Passage during which they were herded on overcrowded ships in the most insanitary conditions imaginable which many did not survive; to their preparation for sale like cattle, the African was completely stripped of his dignity by the traders on the one hand and by the estate owners on the other. On the estates, the Africans were forced to work from daybreak to nightfall, seven days a week until they staggered, but the supervisors and slave-drivers slept where they dropped and ate where they stood. And if they wilted, they were mercilessly whipped like animals, maimed and even killed for the smallest of infractions.

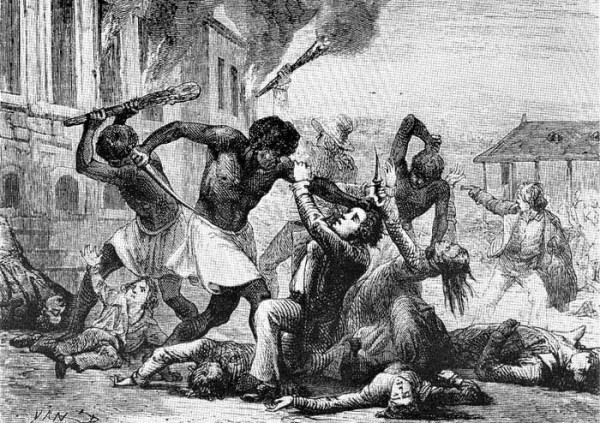

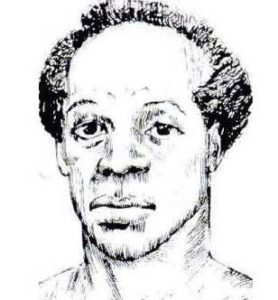

The wealth of the West Indian planter became a kind of legend. The large estates were villages in themselves dominated by the Great House built in the elegant style of the day, while the enslaved lived in barracks close to the sugar works and the animal stables. Eighteenth century plantation life being founded and maintained on force was one dominated by fear. Despite the tyranny and sub-human conditions which held the enslaved African in bondage, he never accepted his lot without a struggle. From individual acts of violence inflicted on themselves and on their white supervisors and masters, to escape to the impenetrable mountain regions to join their maroon brothers, whenever they could, the enslaved rebelled killing their masters and destroying the hated plantation. One of the biggest and most daring revolts took place in the parish of St. Mary in 1760 spreading throughout the island . Led by Tacky who had been a Chief in Africa, more than 400 people lost their lives before peace was restored.

As the 18th century drew to its end, so did the system of plantation slavery. In Britain, the movement led by William Wilberforce resulted in the abolition of the trade in Africans in 1807. Although the trade continued illicitly for some years after, cut off from their regular supply of cheap labour combined with pressure locally from the non-conformist missionaries and increasingly bold acts of resistance by the enslaved, slavery and the plantation system that it supported came under increased pressure resulting first in the partial abolition of slavery in 1834 and its complete demolition in 1838.

Historians agree that the hastening of Abolition Act of 1834 was in no small part influenced by the ‘Christmas Rebellion’ which took place in the western parishes from December 28 1831 to January 5, 1832, triggered by the belief among the enslaved that the colonial authorities had granted freedom but it was being withheld by the local plantocracy. Its leader was a young enslaved Baptist Deacon, Samuel Sharpe who advocated a peaceful protest strike. However, matters got out of hand beginning with the burning of Kensington estate located in St. James which triggered the burning of 16 other estates in the west after which the rebels began roaming the countryside and randomly destroying other estates. This forced the planters to flee their estates leaving tens of thousands of enslaved suddenly free with no co-ordinated plan or leadership. The rebellion created panic in the rest of the island and was not quelled until January by reinforcements of the military. In the aftermath it is estimated that over 300 enslaved were executed while over 1000 were killed by soldiers. Only 16 white colonists were killed. Among the last of the executions was that of Sam Sharpe who though admitting responsibility had throughout advocated protest by way of a peaceful withdrawal of labour at the outset. Sam Sharpe is today recognized as one of Jamaica’s National Heroes.

With emancipation, sugar production fell sharply and the old plantation economy began to decline as estates were sold for what they would fetch. With their newly won freedom the former enslaved left the estates in droves and with the assistance of the missionaries which had been their only allies during slavery, founded new communities in what were called Free Villages throughout the island, signaling the foundation of a new social order of proud free Jamaicans. In the 1840s an attempt was made by the planters and the colonial authorities to find alternative sources of cheap labour without the underpinning of slavery. First labourers were imported from China but were found to be totally unsuitable for the rigours of estate labour. Many returned home while others stayed in Jamaica and turned to other occupations particularly shopkeeping earning them the reputation of being Jamaica’s “shopkeepers”. With the failure of the Chinese experiment, the authorities turned instead to the Indian sub-continent and began replacing the Chinese with Indian labour under a system of indenture. This system allowed for their passage back home to be paid by their employers once they had completed their ‘indenture’ but like the Chinese many of these Indian labourers chose to remain and make Jamaica their home. It was this system of Chinese and Indian indenture that led to the infusion of an Asiatic element in the Jamaican population and the source of the creation of a nation of mixed races.

The period between the full abolition of slavery in 1838 and 1865 the year of the celebrated uprising in Morant Bay were extremely difficult ones for the African Jamaicans. While the white planters received compensation from the British government for the loss of their property (the enslaved) the African Jamaican was left to fend for himself with no resources – financial or educational – and no support from the colonial authorities, condemning him to start life entirely from scratch. When they were forced out of dire necessity to seek employment on the estates they were paid less that subsistence wages and squeezed mercilessly by a vengeful planter class. To add to their distress, the Civil War in the USA had cut off supplies of their staple foods, while severe droughts ruined their own cultivation. Their appeal to the colonial authorities in England fell on deaf ears, as it did on the local Legislature which dominated by the plantocracy and a few Free Coloureds. Matters came to a head in October 1865 with a rising in the parish of St. Thomas in the East which has gone down in the colonial history books as the Morant Bay Rebellion.

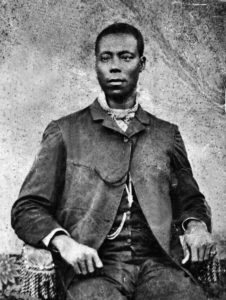

Led by yet another Baptist deacon, Paul Bogle, the so-called rebellion in no way matched the size, extent or violence of earlier protests either the Tacky-led slave revolt of 1760 or the Sam Sharpe-led protest of 1831-32. What distinguished the Morant Bay uprising from other previous disturbances was the brutality and severity of the official response. It was not enough for the authorities to execute or shoot over 400 Jamaicans and to publicly flog hundreds more but white vengeance was seen at its worst in the destruction of over 1,000 dwellings of African Jamaicans. Paul Bogle and George William Gordon, a prominent coloured legislator whom the Governor Edward John Eyre blamed for the trouble were both hanged. A century later, both Bogle and Gordon were to be declared National Heroes.

The events in Morant Bay and their aftermath caused an outcry in Britain and frightened the white power-holders who made up the local legislature into meekly surrendering the old constitution in exchange for handing back to Britain responsibility for governing the island under a system of Crown Colony government – the purest form of colonialism from which there was no major change until 1938.

But in some ways Crown Colony government had its benefits. Largely because of the wide powers they wielded, the British appointed Governors of this period were able to push through reforms and improvements of far-reaching importance. Local government was re-organized, the judicial system completely overhauled and an up-to-date police force formed. Education, health and social services were greatly improved. Roads, bridges and railways were built and cable communications with Europe established and the capital was moved from Spanish Town to Kingston.

It was during this period too that the banana trade was established in the eastern end of the island rapidly replacing sugar as the main export crop and bringing new wealth to the small farming communities of Eastern Jamaica. More significantly it dramatically changed Jamaica from being the mono-crop economy it had been from the early days of the English settlement of the island. The banana trade also had another important economic spin-off and one that would have long-term implications for the country’s growth and development, that is, the establishment of the tourist industry. For instead of sailing empty to Jamaica to collect its cargo of “fruit” the so-called banana boats began to carry holiday-seekers from the US East coast which in turn led to the building of hotels and other accommodation and the exploitation of the natural features of the parish of Portland in particular rafting on the Rio Grande.

The outbreak of World War 1 brought this period of Jamaica’s history to an end. By the 1930s the island was moving towards another crisis. Distress caused by the worldwide economic depression; the ruin of the banana industry by Panama Disease, falling sugar prices, growing unemployment aggravated by the curtailment of migration opportunities and a steeply rising population growth-rate were among the contributing factors. As on every occasion up to this point over its recorded history change was to come only after violent protest. The riots of 1838 were a popular protest against low wages, lack of secure job opportunities, and the general lack of social status.

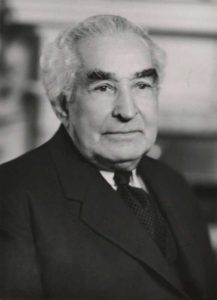

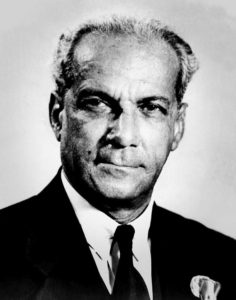

The vast majority of African Jamaicans was still voteless and voiceless . Strikes broke out spontaneously throughout the island and were accompanied by sporadic rioting. Ten strikers were killed, scores arrested including Alexander Bustamante who put himself forward as the defender of workers rights. Busta as he came to be affectionately called, at the time ran a quiet money-lending business in Kingston in May 1938 formed the Bustamante Industrial Trade Union (BITU) and four moths later, his cousin Norman Manley, then the island’s leading barrister, launched the People’s National Party (PNP).In reverse order Busta’s union was to give birth to his own political party, the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) while Manley’s party was to give birth to two trade union affiliates, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) and the National Workers Union (NWU).

The rise of labour to political power was a new and dramatic development and its leaders pressed not only for increased wages but for political reform as well. One result of this was the new constitution of 1944 based on full adult suffrage by which the Crown Colony period was brought to an end. Further constitutional advances followed in 1953 and again in 1957 providing for Cabinet government and virtual internal self-rule, while by 1959 the island was self-governing with only defense and international relations retained by the colonial government. These constitutional advances coincided with other important developments which were essential to the course the island was eventually to follow.

These included the development of natural resources notably in the field of bauxite mining ; industrialization and the expansion of the tourist trade; the growth of nationalism and the establishment of the University College at Mona which was later to achieve full university status as the University of the West Indies. During this period also, with the encouragement of the British colonial authorities, Jamaica flirted with the experiment of a closer association with other countries of the British Caribbean in the ill-fated West Indies Federation. The Federation came into being in 1958 but within three years Jamaica by referendum opted for withdrawal . The British government offered no objection and on August 6, 1962 formally granted it a constitution making the island a fully independent sovereign state.

More on Jamaica History