INCORPORATING ART, LITERATURE, DANCE AND THEATRE AND ITS FOLK CULTURE

A description of Jamaica’s culture requires a separation of its contemporary forms of culture as expressed in art, literature, theatre, music etc. from its traditional folk culture preserved in folk tales, songs and music, proverbs, legends and superstitions.

Up to the 1930s there was little that could be described as Jamaican culture. It should be remembered that Jamaican society was built from scratch and although its majority ethnic group originated on the African continent, the enslaved Africans not only came from different cultures but were further separated from each other and distributed to different plantations. For the socially, politically and economically dominant Euro-Jamaicans, they saw Britain as home and Jamaica as a place of exile.

If we define culture as the social heritage of a community that is, the total body of artefacts, its systems, ideas and beliefs and the distinctive forms of behaviour, then up to the 1930s Jamaica’s social heritage did not exist because the systems were designed to perpetuate social and economic differences not to promote unity.

It was not until the 1930s and 1940s that the country witnessed a powerful surge of creative energy that impelled Jamaicans of all classes to think of Jamaica as “my country” and of Jamaicans of all colours as “my people”. This impulse came from Jamaicans’ discovery of their identity and this brought into being a literature, an art movement and wide-ranging activities in sports comprising a nascent but distinctive culture.

The underpinnings for nurturing this cultural explosion were laid back in 1880 when then Governor Sir Anthony Musgrave established the Institute of Jamaica for the encouragement of Literature, Science and Art which was later to become the catalyst and activator for Jamaica’s art movement. Today, the Institute of Jamaica is not only the repository of the island’s culture, but houses the National Library – the centre of legal deposit for all published materials, and the West India Reference Library housing the best collection of historical materials on Jamaica and the former British West Indies. The annual Musgrave awards presented to outstanding Jamaicans in the fields of Art, Literature and Science remains an important part of the country’s cultural calendar.

One of the earliest recipients of a Musgrave medal was the writer Claude McKay who received the Silver medal which was the highest award at that time. Born in 1890 in rural Clarendon, McKay’s Banana Bottom is regarded by many as the country’s finest novel. He is however more famous as a poet. McKay’s best known poem ‘If We Must Die’ became an international anthem of resistance and was even quoted by Sir Winston Churchill in a World War 2 address to the US Congress, encouraging Americans to join the fight against Nazism.

McKay was the forerunner of a generation of poets and novelists numbering among them George Campbell, Vic Reid, Roger Mais, Andrew Salkey, Sylvia Wynter and John Hearne. They were followed in turn by a later generation which included poets A.L Hendricks, John Figueroa, Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris (who was later to be named Poet Laureate) Denis Scott and Anthony McNeil among others. The outstanding dramatists to have emerged were Trevor Rhone of ‘Smile Orange’ fame and Perry Henzell who directed ‘The Harder They Come’ destined to become Jamaica’s first cult film.

From the 1980s onward, the women began to dominate the literary field particularly in poetry with the likes of Velma Pollard, Pamela Mordecai, Jean Binta Breeze and Lorna Goodison (currently Jamaica’s Poet Laureate) and novelists Olive Senior and Erna Brodber. Not to be outdone outstanding male literary figures re-emerged in the persons of Colin Channer, Kwame Dawes, Marlon James and Kei Miller.

In the Diaspora, literary voices with Jamaican connections were also being heard. These included Zadie Smith, Andrea Levy, Michelle Cliff and Malcolm Gladwell.

Unquestionably one of the catalysts for the revival of Jamaican literary output has been the Calabash Literary Festival. Founded in 2001 by Colin Channer, Kwame Dawes (son of novelist Neville Dawes) and Justine Henzell (daughter of Perry Henzell) Calabash has been held in the last week of May at Jakes Treasure Beach in St Elizabeth. It began as an annual event but is now held bi-annually. Calabash has helped to give Jamaican literature a renewed profile and an opportunity for upcoming writers to share a stage and rub shoulders with accomplished published writers of international repute.

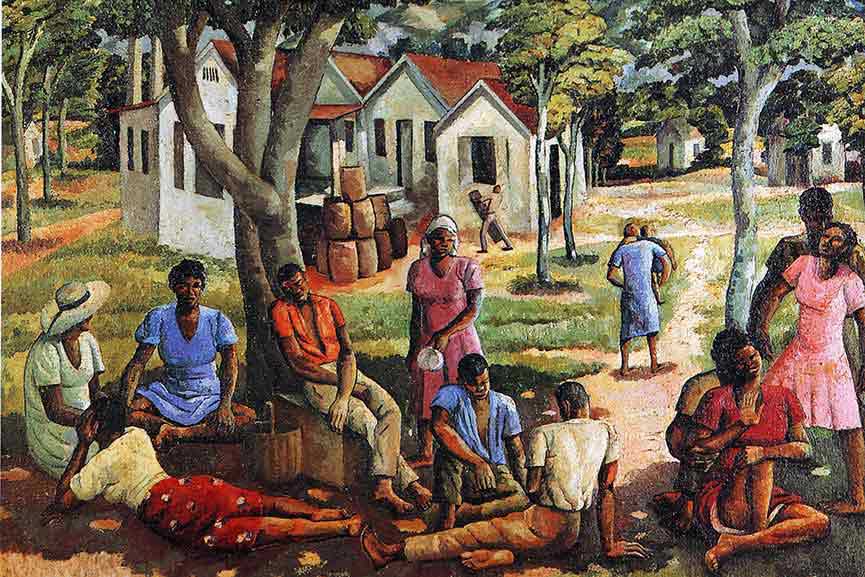

Evidence of a cultural awakening in the ‘30s and ‘40s was first seen in the art movement. It brought together the first group of artists including the young Albert Huie from Trelawny, mature master barber, John Dunkley, Edna Manley, Ralph Campbell and Carl Abrahams. Edna Manley’s ‘Negro Aroused’ and Dunkley’s portrayal of what Black protest was about, marked the beginning of the Jamaica art movement. The great collection accessible at the National Gallery in downtown Kingston presents a portrayal of the Jamaican people during this period of nationalist awakening. Carl Abrahams, Karl Parboosingh, the sculptor Alvin Marriott, the revivalist preacher Mallica ‘Kapo’ Reynolds and the potter from Portland Cecil Baugh, are among the honoured names today of the men and women who in one generation told the story of the Jamaican people in splendid works of art.

Over the years, new generations of painters, sculptors, potters and ceramists emerged in Barrington the Master painter, Eugene Hyde, Osmond Watson, Gloria Escoffery, Judy MacMillan, Colin Garland, Alexander Cooper, Gene Pearson, Laura Facey,Norma Harrack among others.

In the period between the 1930s and the coming of Independence in 1962 a number of organizations were established that helped to institutionalize culture. Joining the Institute of Jamaica and Jamaica Welfare Limited (now the Jamaica Cultural Development Commission) were the Little Theatre Movement (LTM) in 1941, the Jamaica Library Service in 1949 and the National Dance Theatre Company in 1962.

The National Pantomime, traditionally opens on Boxing Day was originally staged at the Ward Theatre downtown Kingston until it fell into disrepair and was moved to the Little Theatre on Tom Redcam Avenue. The Jamaican pantomime combines traditional culture with the latest music and dances while satirizing leaders and current events. Plans are afoot for the restoration of the Ward Theatre which along with adjoining Simon Bolivar Cultural Centre, Liberty Hall , the Coke Methodist Church, the Kingston Parish Church and St William Grant Park form an enclave of cultural institutions in close proximity to each other.

More recent additions to the local cultural fare includes the ‘roots theatre’ phenomenon – raunchy humorous plays which draw large audiences, giving enjoyable and at times thought-provoking looks at contemporary Jamaican life. Roots plays are the mainstays of a vibrant local theatre scene creating a wider audience for more serious fare.

Dub Poetry is another relatively recent addition. Dub poetry is poetry set to music with the emphasis placed on the stripped-down drum and bass rhythm. It has revolutionized poetry in Jamaica by moving away from the formal European tradition and shifting to indigenous Afro-centric interpretations. It employs the vernacular to express the experience of the people while using formal English to cover the full spectrum of emotions and thoughts. Some of its best known exponents are Yasus Afari, Jean Binta-Breeze, Mutabarujka, Linton Kwesi Johnson and Benjamin Zephaniah.

Another long-standing event is the Jamaica National Festival of Arts which dates back to 1955 and has been an annual event since 1963. It culminates in a period running from Emancipation Day on August 1 to Independence Day, August 6. Organized by the Jamaica Cultural Development Commission, the JCDC’s extensive programmes of training have developed along with national contests in song, dance, speech and drama, the culinary and visual arts. Performances show a blend of traditional and contemporary art forms and overall represent the best display of Jamaica’s folk culture.

A crucial role played in the training of artists in all genres is the Edna Manley College for the Visual and Performing Arts. It is the successor institution to the Cultural Training Centre that was established in 1976 which at the time brought together four institutions: the Jamaica School of Art, the Jamaica School of Drama, the Jamaica School of Dance and the Jamaica School of Music. In 1995 the Centre was renamed the Edna Manley College in honour of the renowned artist and sculptor, Edna Manley. The School offers a Bachelors degree in the four disciplines in collaboration with the University of the West Indies.

Folk culture

Jamaica’s folk culture consists of Folk Tales, Proverbs, Dance and Music, Legends and Superstitions.

Folk Tales are predominantly Anancy stories of which the central character is Br’er Anancy, the spider man. The name anancy (Anansi) comes from the African Twi, meaning spider, his wife Crooky and his son Tacooma. Anancy’s main characteristic is trickery. Though small and weak physically, he uses his ‘brains’ to get the better of others and seldom loses. He personifies the triumph of the weak over the strong which would have been a comforting mythology during the days of slavery.

Anancy stories always begin with the English formula ‘Once upon a time’ but end with must be an African one ‘Jack Mandora, me no choose none’ – an assurance that any resemblance between characters in the story and living people, especially those present is purely coincidental.

DID YOU KNOW?

There is a superstition about not telling Anancy stories in the daytime as this would bring bad luck.

Proverbs reveal a lot about Jamaica’s history and the characteristics of the people, epitomizing Jamaicans’ humor and wit, his acumen and aspirations and in them are ridiculed his faults and his failings. Proverbs fall into four categories: those of African origin e.g. greedy choke puppy in the West African version (a huge morsel chokes a child); those originating in the Caribbean; those adapted from European proverbs and those clearly European in origin but expressed in local idiom.

Jamaican proverbs are colourful and vivid. In his proverbs the Jamaican endeavours to justify the vicissitudes of life. A no because cow no hab tongue mek cow no talk’ (silence is often born of prudence rather than ignorance) or alligator lay egg but him no fowl (do not be deceived by appearances); rockstone a river bottom never know sun hot (only those who know hardship can sympathise). Sof’ly Sof’ly catch monkey runs the proverb and howdy and tanky bruk no square (Courtesy hurts no one) are easily understood.

Music is perhaps the most revealing form of folk expression. It’s frank, natural and spontaneous, springing from the soul of the people and often reflecting historical circumstances. They include ‘work songs’, ring tunes associated with children’s games, ballads, revivalist hymns and calypsoes. Among the best known are Day-O, the banana worker’s song; Mango Walk and Linsted Market. Colon Man is a reminder of the Jamaican constant quest for work overseas and War down a Monkland refers to the 1865 Morant Bay Rebellion. ‘Digging songs’ have a distinctive tempo suited to the rise and fall of hoe and pickaxe. They are a great aid to labour making the time seem short and the work light.

Legends and Superstitions are an integral part of the folk culture. One of the most persistent is the legend of the Golden Table. This is said to lie concealed at the bottom of many of our rivers and deep silent ponds. This fabulous table, rich beyond imagining is said to appear briefly from time to time to tempt weak humans with desire. But it is better never looked upon and best let alone because it is unattainableand to pursue it is to pursue disaster. Another centres on a water spirit known as a ‘River Mumma’. She is believed to inhabit deep pools and like the mermaid she emerges at times, sits on a rock and combs her long black hair. She will plunge back into the water at the approach of a human, sometimes forgetting her comb which it is most unwise to touch as she will return for it.

Then there is the ‘Spanish Jar’ which is a large earthenware container that was in the past used for storing water. Legend has it that the Spaniards at the time of the English invasion, buried their treasures in such jars, leaving behind as guardian the duppy of a murdered slave who had first been forced to dig the hole. If the treasure is meant for you, the duppy will ‘dream to you’ revealing its hiding place. Otherwise, even if you have discovered its hiding place, you may dig and dig but the jar will sink farther and farther into the earth. The belief in duppies or ghosts lies at the heart of Jamaican superstition. A duppy can be set on a living person to cause misfortune, injury and even death. Fortunately, if discovered in time another duppy can be employed to counteract the former. Other bad spirits of the night are ‘rolling calf’, ‘three foot horse’ ‘whooping boy’ and ‘old hige’.

Two 18th century personalities who became legends in their own time are Nanny the Maroon chieftianess and the Highwayman, Three Finger Jack. It is aid Nanny never went into battle armed but received the bullets of the enemy that were aimed at her and returned them with fatal effect.

Jack Mansong known as ‘Three Finger Jack’ because of a hand injury suffered in a fight with a Maroon called Quashie. After leading an unsuccessful slave revolt, Jack himself managed to escape to the mountains of St Thomas where from his hideout, he terrorized the island by his daring robberies. Nearly 7 ft. tall, amazingly strong with a long face and fierce black eyes, Jack is said to have carried a small bag of obeah the Jamaican form of black magic which made him invulnerable.