After his cherished childhood nanny dies, a Jewish young man entering into adulthood realizes there is so much he has yet to learn about the woman who lent him her accent and with whom he shared an unlikely kindred spirit. From New Jersey, USA to Jamaica, Ross Kenneth Urken chronicles the life of Dezna Sanderson, the Jamaican immigrant nanny who had an outsize positive effect on his dysfunctional Jewish American family. Dezna became Urken’s closest confidante and inspired in him a love of words and narrative, but she vanished before he could ask her all the essential questions he wanted about her life – adult to adult. There was a tacit privacy agreement she maintained during his childhood, a sacrosanct code of silence. Her role was to maintain order in his American household while obscuring the chaos of her own past. As redemption for his missed opportunity, Urken goes on a quest to find her through an authentic connection to her Jamaican homeland and her family members, digging deeper into her family life – the three loves, the eight children and the hardships she faced in Jamaica. In his quest for the truth of Dezna’s past, Urken encounters unexpected secrets and a spiritual land.

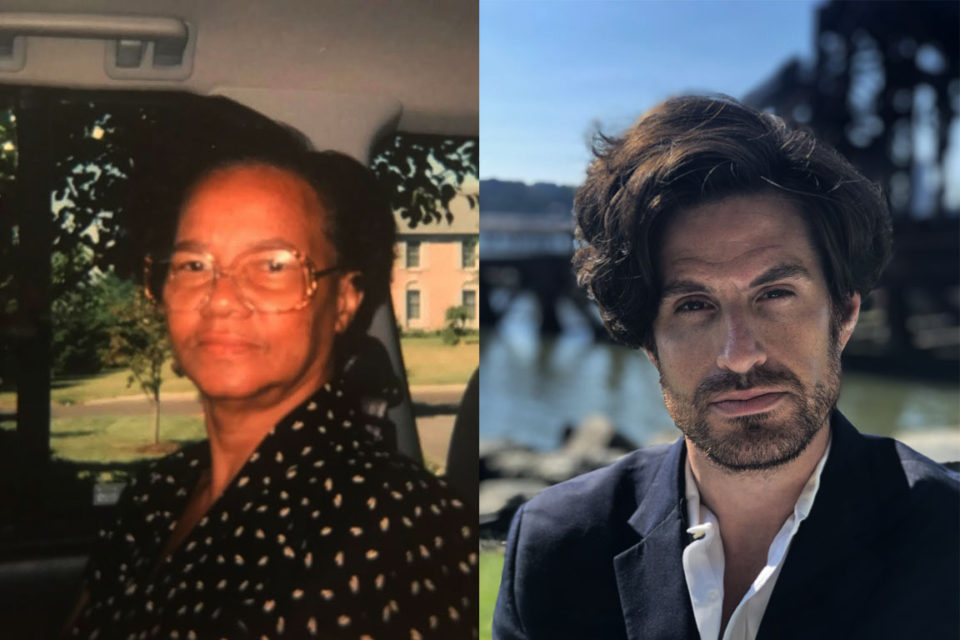

All of this is lovingly told and beautifully written in rich lyrical prose in the book entitled Another Mother coming to a store near you this October and which can be ordered now on Amazon.

In the following interview with Jamaica Global Online Ross Kenneth Urken talks about the process of writing this memoir, the challenges he encountered and what his expectations are about how readers will receive his first full-length book. The surprises continue in this interview!

– Can you describe the writing process? Was it all in one go or did you do it more gradually as inspiration allowed?

In my early twenties, I had written an initial essay as a tribute to Dezna while she was alive, and as I note in the book, I shared it with her during our final Thanksgiving together. Though I revised the essay after her death, I didn’t necessarily aspire to turn this story into a book-length project. But the more I learned about Dezna in connecting with her children, the more I realised how little I knew of her origins. As I say in the book: ‘My understanding of her life was, at best, a vague approximation, like my conception of Celsius temperatures.’ Spending time with Dezna’s family in New Jersey and then Jamaica in my mid-twenties nudged me to delve deeper. But I was hesitant to take this on as a memoir, because I knew it would be exhausting emotionally. And I had already written a non-fiction book right after college that I dubbed “The Friday Night Lights of tennis set in North Carolina.” Prematurely agented, I’d even been called into a major  publisher’s office in Manhattan – boychik could hardly grow a full beard at that point – and seemed primed to publish my first book. I did the literary equivalent of the Deion Sanders touch celebration, hand behind my head toward the endzone. Ultimately it didn’t pan out after so much time invested, and I wanted to make sure if I took on another big project, I could see it to fruition. So I basically tricked myself into writing this book. I first told myself I was writing a proposal. Then I did a twenty-page treatment. Then I wrote three sample chapters. I ultimately mapped out a structure with chapter summaries. The book alternates between memoir chapters about my childhood with Dezna and modern-day encounters with her children that allow for flashbacks to different periods of her life. Grounding those glances at the past in my interactions with her eight children seemed an effective way to tie past and present together and weave a through-line between people unrelated by blood but connected through their bond to a strong woman. Little by little, I shaped the material into a book. Dezna instilled in me a resilience. It was a certain doggedness that helped me overcome the inevitable rejections while my agent shopped for a publisher.

publisher’s office in Manhattan – boychik could hardly grow a full beard at that point – and seemed primed to publish my first book. I did the literary equivalent of the Deion Sanders touch celebration, hand behind my head toward the endzone. Ultimately it didn’t pan out after so much time invested, and I wanted to make sure if I took on another big project, I could see it to fruition. So I basically tricked myself into writing this book. I first told myself I was writing a proposal. Then I did a twenty-page treatment. Then I wrote three sample chapters. I ultimately mapped out a structure with chapter summaries. The book alternates between memoir chapters about my childhood with Dezna and modern-day encounters with her children that allow for flashbacks to different periods of her life. Grounding those glances at the past in my interactions with her eight children seemed an effective way to tie past and present together and weave a through-line between people unrelated by blood but connected through their bond to a strong woman. Little by little, I shaped the material into a book. Dezna instilled in me a resilience. It was a certain doggedness that helped me overcome the inevitable rejections while my agent shopped for a publisher.

– How long from resolving to make this a book and completing the first draft?

Two and a half years, give or take. I have a day job and a busy travel schedule, so it was in fits and spurts, writing early in the morning and writing late at night. I let passages and chapters marinate and returned to them. I took advantage of isolated time on airplanes and in hotel rooms from Norway, to Japan, to China, to Jamaica. I am a slow, deliberate writer. I agonise over every word. Trips to Jamaica were often paired to see Dezna’s family with other assignments. In fact during the same trip to Jamaica for the headstone laying ceremony for Dezna that I recount at the end of the book, I went to Kingston for The Washington Post to interview Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce ahead of the Rio Olympics.

(Note: Ross Kenneth Urken is a journalist who has written for The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Paris Review,The Wall Street Journal , The Atlantic, Newsweek, National Geographic, the BBC, The Guardian, Sports Illustrated, among others).

– In the book, it seems you sometimes feel more at home in Jamaica than New York City where you live. Why is that?

New York has a frenetic energy that I find stimulating, motivating, and stressful. It fuels me, but I often seek refuge in the quiet parts of Lincoln Square, my neighbourhood, by the Hudson. Jamaica, generally speaking, packs that same vibrancy across the island but channels it in a calmer way. There’s so much hustle in both places – securing the next gig, snagging the next opportunity. But in New York, there’s an obsession with speed, getting to the next destination, side-walk walk-offs, a true faster-is-better mentality. In Jamaica, the journey itself seems to attract a certain reverence. I operate on island time. I’m inveterately late. I enjoy the process.

I find Jamaican communication much more direct than what you find in New York or the US in general. Americans are circumlocutory, euphemistic. Jamaicans are straight-shooters, which I find refreshing. I feel much more comfortable with that kind of communication where the letter matches the spirit.

– How has your career as a travel writer informed your approach in this book?

As a travel writer, I am often parachuting into a place for just a couple days at a time. As a result, I try to be extra sensitive to avoid generalizations and broad-strokes conclusions about a certain location or group of people. Openness and empathy are my most important tools in my trade. Letting down my guard and simply being with people as I pursue a narrative proves invaluable. Sometimes I think being a writer is like being a phlebotomist. It’s best to put people at ease and allow them to forget a recording device is involved. I think injecting a certain sensitivity into my approach helps me avoid what some deem ‘drive-by anthropology’, where an American writer comes to an ‘exotic’ place and observes it as if through aquarium glass. The most effective way to avoid that pitfall is to maintain authenticity, not by speaking to tour operators or hotels – who can prove to be quite knowledgeable, of course – but locals from all walks of life. I do believe it’s possible to distill a sense of place even after a short visit, but it takes work, true shoe-leather.

My childhood with Dezna, replete with ackee and saltfish breakfasts and patois expressions, made me wildly curious about other cultures, other ways of life. I’m fascinated by what makes certain parts of the world tick. In that process, my stomach often leads the way. When I am exploring a place – whether in Africa, Asia, South America, or Europe, say – I often use Jamaica as a compass. Besides the US and Russia, France, and Mexico where I did study abroad programs, it is the country I’ve spent the most time in and the one that obviously has most captured my heart. And my discovery of culinary, linguistic, historical, environmental, economic, and cultural elements helps me seek out that richness elsewhere.

– This is a deeply personal book. Can you elaborate on how you accessed some of those emotions and memories throughout the writing process?

As I note in the book, as an anxious child I benefited from Dezna’s calming influence. But I still went to therapy for three main reasons at different parts of my childhood to overcome OCD, panic attacks, and aviophobia. I write at length about those challenges throughout my memoir and how they dissipated amid Dezna’s presence and amplified during her absence, but what I don’t address is my return to therapy to unpack some of the emotional baggage and reminiscences during the genesis of Another Mother. In New York, a therapist is like a barber; everyone has one. I’m most comfortable expressing myself by moving my fingers on the keyboard. Openly discussing some of these weighty subjects, even with friends, proved difficult, but tonic. But having a degree of separation with a relative stranger while lying on a couch allowed for a certain fluidity to my thoughts. It helped me metabolize those emotions and place them on the page more delicately.

– In the book you address how Dezna’s children have become like siblings to you. Was there a moment when you finally felt accepted as part of the family?

I finally felt accepted by Dezna’s children when they started to make fun of me. Once I posted a photo on Facebook of myself in a trench coat and wearing new spectacles. ‘O.K., inspector?!?!’ commented Carla, Dezna’s second-youngest daughter. That kind of ribbing has become legion in my interactions with Dezna’s children and it’s helped to make me feel like part of the family. I won’t ruin the ending, but in the final chapter of Another Mother, I mishear a particular Jamaican curse word as my own name, which has similar phonemes. Orville, Dezna’s second oldest son, was particularly amused at my own expense – in a good-natured way, of course. That the family members feel comfortable finding humour when I make a bit of a fool of myself, which is often, makes me feel fully integrated as a younger brother.

– Which readers do you think this book will resonate with the most?

I speak about my book with anyone who will listen – strangers in my travels, co-workers at my day job, my coffee cart baristas. And I find that it tends to resonate universally, because ultimately it is a narrative about family. Whether people grew up in ‘Leave It to Beaver’ innocence or in a more difficult home, families are complex; exploring a narrative about one family in depth allows readers to reflect upon their own and map out particular quirks in certain relationships. In Another Mother, I riff on Tolstoy’s opening “All happy families” line from Anna Karenina. In my experience, I’ve found that the families in which everything seems honky-dory also have secrets and unsavoury elements. We become adults when we really start to see our parents for who they are – the beautiful qualities mixed with the foibles. Some agents and publishers expressed concerns that this book might only appeal to a niche segment of the population – those with Caribbean ties and origins or those who grew up with nannies. But everyone has a family or had one.

I also think it is a near universal experience to have a teacher, a coach, a friend’s parent, or some other mentor who provides invaluable support at a point in someone’s life when he or she most needs it. I think, more often than not, we do not as kids understand what shaped those people’s lives and how their own influences informed our own sensibilities. It is my sincere hope my sondage in Another Mother might intrigue others to explore those mysteries in the lives of their own heroes.

– You worked with a Jamaican publisher to bring this book to the world. Did you encounter any advantages over working with an American publisher?

I once visited an astrologer in Nepal who prognosticated my book would be an international success. Now, working with Ian Randle Publishers, I have a book that is actually being distributed to more than 20 Caribbean nations, along with parts of Africa, the UK, Canada, and the US. That’s been quite a thrill and lends credence to his words. The guru is never wrong, apparently.

Working with IRP has also brought an extreme level of authenticity to my narrative. I misnamed one particular plant in the American way, and my editor set me straight. Ditto my rendering of a particular plaza in MoBay, where I often get lost. My editor made sure I had every alley and side street down pat. And because there is a considerable amount of patois in the book, it was important to have fluent speakers examining the spelling.

Of course, my vernacular occasionally proved unfamiliar. To appear uncool, which for me takes little effort, I made an oblique reference to a spliff. “What is jazz lettuce?” my editor questioned after her first pass-through. I originally wrote this book with American spelling, but when Ian Randle Publishers accepted my manuscript, we changed to British orthographic conventions. The book immediately seemed much more sophisticated.

– How do people react when you talk Jamaican? And do you ever unwittingly blend in Jamaican expressions when you speak American? And is the Jamaican in you – talk and otherwise – stronger or weaker as you get older?

An acquaintance who recently learned about the true origin of my accent had a eureka moment. ‘Oh that makes sense,’ he said. ‘I’d just thought you had the last of the male Audrey Hepburn accents.’ Dezna’s accent was one of the St Elizabeth hills, a bit subtler than the stereotypical ‘Cyaribbean’ accent Americans might encounter in film. What remains on my tongue is, as a result, perhaps difficult to place.

There’s also a particularly jarring question I’ve been asked at parties on more than one occasion: ‘Your English is so good – how long have you been in the States?’ I think there’s a certain foreignness to my inflection and the cadence of my speech. I can see in people’s eyes a certain GPS-recalibrating wonderment.

Though my childhood was peppered with patois expressions and Jamaican aphorisms, I do not speak fluent patois. I understand pretty well. But I do employ Jamaican expressions here and there. As a valediction – both electronically and in person – I often say “blessings”, and that’s the one that tends to throw people. It is such a sincere offering that it can be confusing – especially in city like New York full of jaded people who view earnestness with great skepticism.

– From your personal experience, what lessons, if any, are to be learned about the value of the immigrant contribution to the raising of the American family and to cultural diversity in the country?

I thought about making the book a lot more politically deliberate in a celebration of immigrants at a time when the US is contending with a dangerous and racist president. In fact, in an earlier draft, I directly entered the fray of political discourse. But I ultimately thought some of that soap-boxing distracted from the heart of the narrative and its emotional current. From the ultimate presentation, the reader can glean my stance on these matters and draw conclusions about the important contributions immigrants have long made to the US.

Coming to America has long been a way for those around the world to seek opportunity. As I explore in Another Mother, Dezna moved to the US under complex circumstances during Jamaica’s volatile ’80s. Like 200,000 Jamaicans during that decade, 10 percent of the population at that time, Dezna sought to provide economic opportunity for her family and more stability. Her courage, assiduousness, and strength are inspiring. But here the US is – putting the children of people on a similar journey in cages. Perhaps by extension, to a certain type of reader, understanding the sacrifices immigrants make can shine a light on the problematic elements of the current immigration policy in the US.

– How has the Jamaican Nanny upbringing shaped you as a person and your world view? Speculate on how different Ross’s life might have turned out without his Nanny’s care and influence?

It is quite easy to conclude I would be an entirely different person had Dezna not been around to shape me during my early years and serve as a source of wisdom as I aged. There is a persistence, a sticktuitiveness Dezna imprinted upon me, to strive for greater achievements, to take pride in my work, to find value in even slight improvements. Her fascination with words and storytelling contributed in no small way to my career as a writer. My exposure to Dezna’s blend of patois and sophisticated received pronunciation also extended the limits of what I found language could do. It strained the parameters of communication and wordplay and tuned my ear to the nuances of subtext in dialogue.

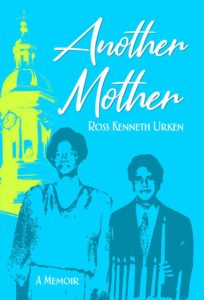

Photos of Ross and Dezna’s Family

If you find this interview fascinating and inspirational, so is the book Another Mother due for release in October from Ian Randle Publishers • Jamaica • www.ianrandlepublishers.com

208 pp • ISBN 978-976-8286-04-8 (cloth) • Price: US$18.00