By Debbie Jacob

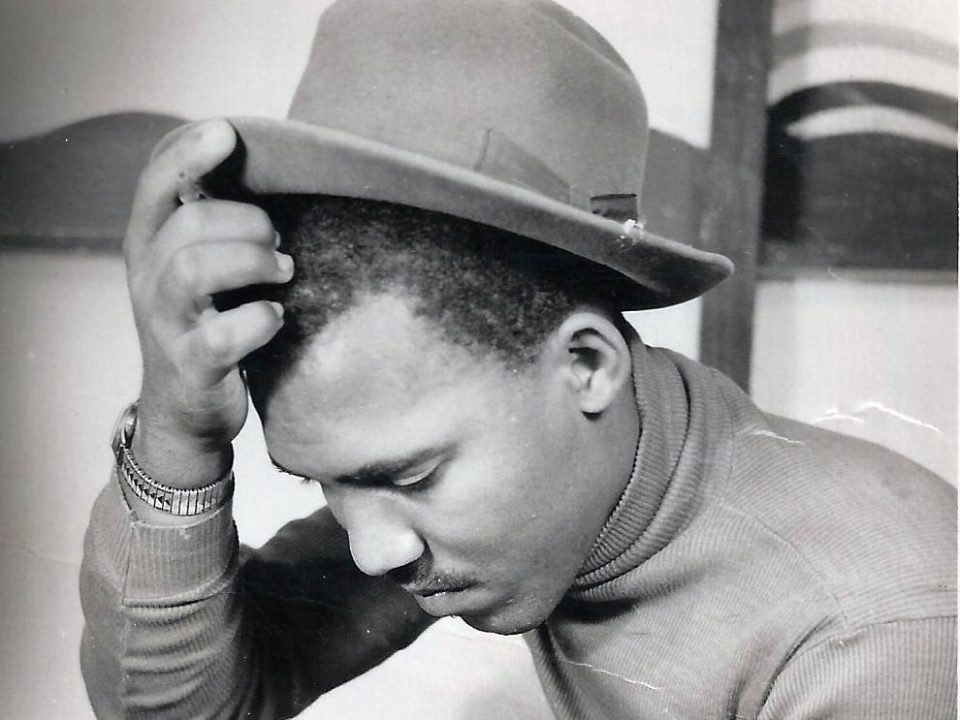

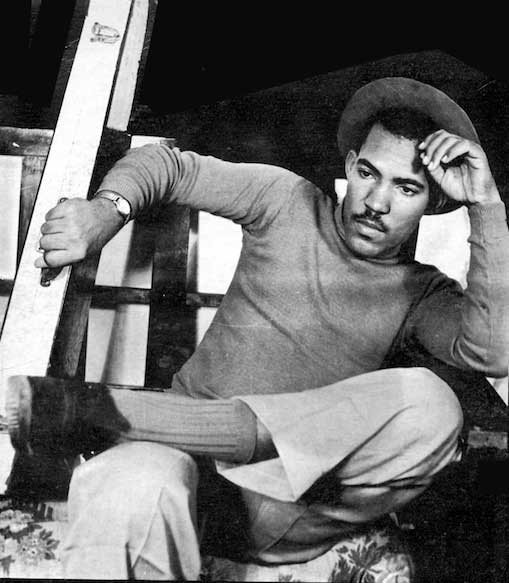

In all the pictures from the 60s, the talented and troubled Jamaican trombonist Don Drummond appears melancholy and aloof. No one ever captured the essence of the handsome young musician who wore a grey felt hat and often performed with his back to the audience. No story ever fully explained his mental issues and tumultuous life. In 1990, I traveled from Trinidad to Jamaica hoping to solve the many mysteries of this enigmatic musician. As a young journalist, I felt up to the challenge.

The story of Drummond’s contribution to the development of ska, his quirky personality, the crime that ended his career and had him committed to an insane asylum and his mysterious death always made compelling reading. Drummond’s defiance of the racial parameters that defined the 60s made him an iconoclast and a hero decades before the Black Lives Matter movement. His story remains an important lesson about fame, creativity, mental health and domestic violence that resonate today.

The front-page story of the Jamaican Evening Star delivered shocking news on May 8, 1969. Don Drummond, Jamaica’s greatest trombonist and music writer died last Tuesday in the Bellevue Hospital where he was an inmate as a criminal lunatic.

In July 1966, Drummond was convicted by an all-male jury in Home Circuit Court of murdering his girlfriend 23-year-old rumba dancer Anita Mahfood otherwise called Margarita. The murder occurred at 4:30 a.m. on January 2, 1965.

Drummond, who was judged insane by the jury, was ordered by Mr. Justice Fox to be kept in strict custody as a criminal lunatic until the Governor-General’s pleasure was known. He was kept at the General Penitentiary for a few days before taken to Bellevue [mental hospital].

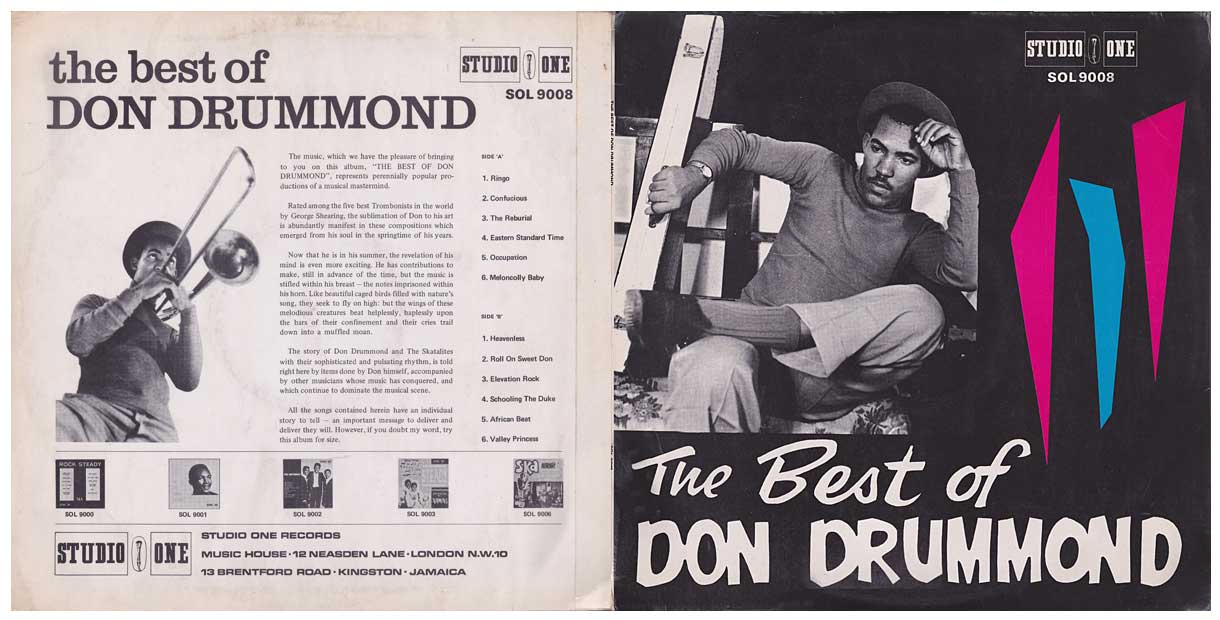

Drummond played an important role in developing modern Jamaican music with compositions like “Eastern Standard Time”, “Roll on Sweet Don”, “This Man is Back” and “Don Cosmic” and “Addis Ababa”.

“Drummond…was the first folk hero of the island’s popular music,” writes Klive Walker in a collection of essays called Dubwise: Reasoning from the Reggae Underground. Walker says Drummond’s popularity stemmed from “…the way he used his music to tap into pain, suffering, joy, and aspirations of his fellow working-class African Jamaicans.”

Like Bob Marley, Drummond had fought his way up from the ghetto. But Drummond and Marley were polar opposites. Taciturn, strange and anti-social, Drummond proved moody, mysterious and bizarrely fascinating while Marley, down-to-earth, personable and outgoing, oozed charisma.

Drummond’s musical influence came to an abrupt halt when he calmly walked into the Rockfort police station and reported Mahfood’s death. Surprisingly, Drummond’s loyal subjects did not abandon him after they learned Mahfood had been stabbed to death. The Caribbean region has never been known for its understanding of mental illness, but Drummond garnered sympathy, which fed a larger-than-life legend of a mentally disturbed, gifted musician.

Initially, Mahfood, a Jamaican with Lebanese roots, was barely mentioned in Drummond’s narrative. It was a sign of the times and the injustice that prevailed against women in the Caribbean.

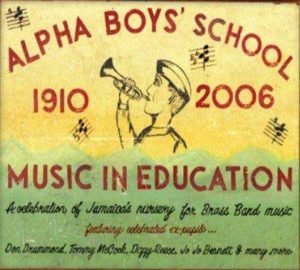

Drummond’s mother, Doris Maud Munroe, a domestic servant, was only 19 when Donald Willis Drummond was born on March 12, 1934 at Victoria Jubilee Hospital in Kingston. His birth certificate lists his father as Uriah Adolphus Drummond, a labourer, born on May 4, 1908. Nothing else is known of Drummond’s life until he entered Alpha Boys school.

His teachers at Alpha Boys served as my starting point for investigating Drummond’s life. Sister Mary Ignatius Davies, Jackie Willacey and Noel Hernan pulled out a green file with two pages of information and a newspaper clipping about Drummond needing a trombone.

His teachers at Alpha Boys served as my starting point for investigating Drummond’s life. Sister Mary Ignatius Davies, Jackie Willacey and Noel Hernan pulled out a green file with two pages of information and a newspaper clipping about Drummond needing a trombone.

“Don was bright and he loved music,” said Hernan, the guidance counselor.

He took courses in gardening, music, tile manufacturing and farming. An entry in 1961 says he was “intelligent, industrious and civil.” He liked cricket, but he mostly liked to go off by himself and play the trombone under a tree.”

Drummond impressed Willacey, his music teacher, with his dedication to the instrument.

“After he left Alpha, Don was in and out of the mental hospital,” says Sister Ignatius, a teacher at the school.

“Record producer Clement “Coxsone” Dodd took him from the mental hospital to the recording studio.

Drummond left Alpha Boys on October 31, 1950, six weeks before graduation to play with Eric Dean and his orchestra, a popular jazz band dating back to 1944. By 1954, he had his own band, the Don Drummond All-Stars. He seemed to be succeeding in spite of all of his mental challenges. [In hindsight, writers speculated he suffered from manic depression or paranoid schizophrenia].

“He used to wear six watches,” said former neighbour Thelma Chandley. “He wore them on his hands and feet.”

Drummond had peculiar eating habits as well. His neighbour Obadiah Arthur told me Drummond would eat a dozen bananas at a time. “Then he’d eat ½ dozen raw eggs. Just suck them.”

He seemingly suffered from the psychological disorder of pica, which compels someone to eat unnatural objects like dirt. In her biography, Don Drummond: the Genius and Tragedy of the World’s Greatest Trombonist, author Heather Augustyn’s sources said he ate clay and dipped bananas in sand before eating them.

Everyone who knew Drummond described him as “temperamental.” Roland Grant said Drummond would call neighbours to hear music he wrote and if they said they didn’t like it, he would become upset and throw the music across the yard. “When he played to audiences, he used to stop sometimes in the middle of a song, take his chamois cloth, wipe off his trombone, pack it up and go,” said Arthur. “Nobody could call him back. He often played with his back to the audience. People loved him though.”

At Studio One, record producer “Coxsone” Dodd talked about Drummond’s first trombone. “Don had just come out of Bellevue mental hospital. I found out he was in perfect musical condition so I gave him a trombone. He always seemed happiest when he was playing or even when he had the trombone in his hand. When I first met him at Federal Records, he had come to audition as a vocalist. What he had wasn’t ready for recording at the time.”

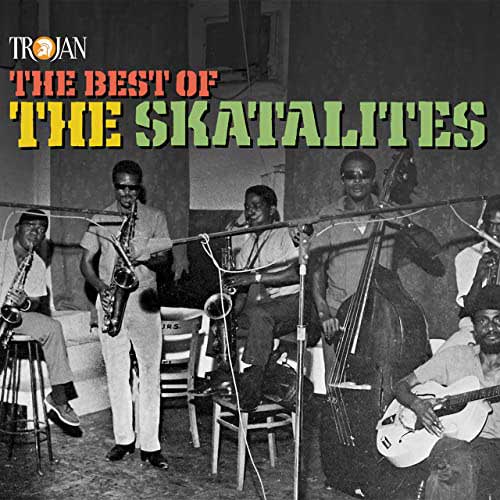

Musician Cecil Valentine “Sonny” Bradshaw said he met Drummond when he played in Eric Dean’s Band Bradshaw remembered how musicians had to buy a pair of glasses for him. He also remembers the marijuana smoking. “Don got into marijuana quite early after he left school. It’s too bad because he had not reached the point of being a good player. There are some myths. He was a folk hero, mysterious. He was a little fellow, a withdrawn person. He didn’t talk to anybody. He clearly had problems, but nobody knows what for sure.” Bradshaw said Drummond could stop playing trombone for months, pick up the instrument and play. “That isn’t done with the trombone.” The Skatalites brought Drummond fame, but his mental problems skyrocketed in the band. “The Skatalites were all temperamental,” said Bradshaw.

Drummond retreated into a dark, lonely, dangerous place. Bradshaw’s story about the night Drummond killed Mahfood differs from newspaper accounts, which say Drummond claimed she had stabbed herself.

“Don said that she did him something wrong and he killed her. Tony Spaulding and I were the first people who saw him the night after they locked him up for killing Margarita. None of his so-called friends went to see him. Spaulding became his lawyer – boy he loved Don bad.” [The future Jamaican Prime Minister PJ Patterson was also Drummond’s lawyer].

“Don was very calm when we first saw him and he said, ‘I just killed Margarita.’ Tony said, ‘You can’t say that,’ but he did say it, and he didn’t want to say that he didn’t do it. He knew what he had done. There was no guilt, no remorse in his voice.”

Yet Bradshaw also described Drummond as “melancholy” at the police station.

“In the trial, Tony recommended Don go to the hospital and that was the victory. They put him in a maximum-security hospital. In there, he was back in the same environment where he couldn’t get well. He was violent most of the time. I used to go to see him. He was looking forward to coming out someday and playing again. He said, ‘I’m going to buy a new trombone.’ He used to talk all the time about getting that new trombone.”

Psychiatrist the late Dr Frederick Hickling, well-known for his work with musicians, said, “Don was just a raw, intense musician, no graces, no frills. Very stirring. Not having his trombone to play while in Bellevue would have affected him a great deal because music was his way of communicating.” When pressed, Hickling told me he had seen Drummond’s hospital files, and there was nothing really extraordinary in them that could pin anything down on his life in the mental institution or how he really died. “It would be a waste of time to try and see his file,” said Hickling. “No one will ever be able to see the file now.”

No one ever did see those files.

Calvin Cameron, who replaced Drummond as the Skatalite’s trombonist said, “Some of the music Don wrote had no clef, no time signature, no bar lines, no stems. Just notes. You just have to play and interpret them yourself. But some of the music was written out neatly and ..in perfect order.”

Not everyone sang Drummond’s praises.

“Drummond was not the kind of guy you want to make a national hero out of,” said radio personality Fred McDermott. “He was hostile towards strangers, and he didn’t like whites. His musicianship was not that great. His music was almost hypnotic because of the repetitious rhythm, simple phrasing and structure and minor phrasing. There’s no doubt he had a profound effect on the music at that time. He was very popular with the people from the ghetto. Drummond became a mystique – the mystic, mad genius. He had a quality that attracted the alienated.” In many ways, McDermott saw Drummond as a symbol of rebellion, a product of disgruntled, alienated youth searching for someone to identify with .“The mistreatment of black males in white society left men with few options. The main characteristic of Drummond was alienation.”

In her biography of Drummond, Augustyn seems to have unearthed burial records for the musician, but she couldn’t locate the grave. “After Don died, his mother came across here and asked the priest to do the funeral,” Willacey told me. “We agreed. There was a big crowd. Someone came into the crowd and claimed they couldn’t take Drummond’s body to bury him. The person said he had evidence that Don was beaten to death in the hospital. A scuffle broke out. They weren’t able to bury him. Somehow the mother got the body away. Later, the mother went quietly and had him buried. I don’t think anyone knows exactly where he’s buried. He was probably buried without a priest.”

No one ever saw Drummond’s mother again.

The work I did in Jamaica vanished from my computer 25 years ago. But in August 2020, I found my printed manuscript, Cry for a Melody. It included a 35-page biographical essay on Drummond and a novel exploring the fine line between creativity and madness. On an old desk in a back room of my house, it lay waiting to be rediscovered in a tense and volatile time marked by racism, violence and growing concern about mental health sparked by the Covid-19 epidemic — all issues Drummond faced 60 years ago. Statues of slave owners, colonialists and racists came tumbling down; historical narratives changed and the Black Lives Matter movement marched on. I wondered how Drummond would be perceived in this brave new world.

Debbie Jacob is a journalist and author of Wishing for Wings and Making Waves: How the West Indies Shaped the US, Ian Randle Publishers and seven other books.

Debbie Jacob is a journalist and author of Wishing for Wings and Making Waves: How the West Indies Shaped the US, Ian Randle Publishers and seven other books.

—

Debbie Jacob

While we have your attention…………………..

The above feature on musician Don Drummond by Debbie Jacob, is the FIRST guest article to be written for jamaicaglobalonline since the website was launched in June 2018. We aim to continue posting feature stories on Jamaicans of distinction both living and deceased at home and in the global diaspora, as well as articles related to the country’s history and culture and national and international developments affecting Jamaicans at home and abroad. Based on the response so far to Debbie Jacob’s article we welcome other guest articles on any subject or theme related to Jamaica and Jamaicans or developments directly affecting their lives and well-being. We are still a non-revenue-earning site so all submissions will be regarded as a gratis. Contributions should not be more than 1,500 words and ideally be accompanied by a selection of related photos and addressed to: the editor at info@jamaicaglobalonline.com.