“A people without knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots”.

Marcus Mosiah Garvey

October is commemorated as Black History Month in Britain as a means of promoting black history both cultural and via heritage as well as to disseminate information on positive black contribution to British society. This month across the UK, over 4,000 events have been organized celebrating black history, culture and achievement, along with activities in the nation’s schools. Unlike the USA where Black History Month is commemorated in the month of February and where the celebrations tend to focus soley on the history of African Americans, in the UK, the month not only recognizes the contributions of African and Caribbean history but that of Asia also.

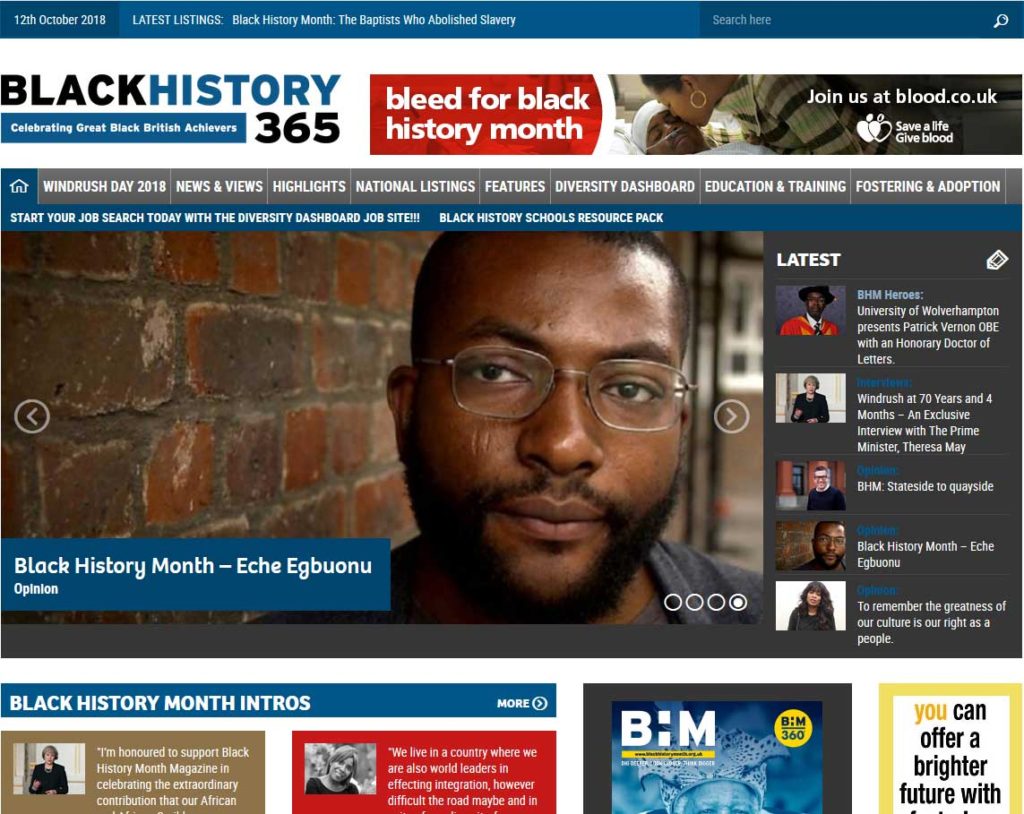

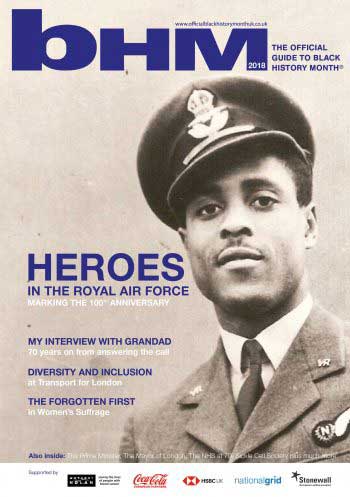

Black History Month (BHM) in 2018 is markedly different from the previous 30 years since it was first instituted in 1987, because it has brought to the fore both the underlying racial tensions in British society as well as the overt acts of Afriphobia – racism against people of African descent – best exemplified by the scandalous Windrush Affair. Describing it as another episode of historic racism directed towards black Britain, activist, Patrick Vernon has observed that since the Windrush atrocity broke in April, the public has learned more in recent months about the Windrush generation than in the previous 50 years.

Cyber Racism

That is why Vernon has no doubt that the hacking of the Black History Month website twice in 24 hours on October 1, the first day of the month’s commemoration, was a direct response to the heightened public awareness of the black British condition generated by the Windrush scandal. Vernon, who is editor of the 2018 edition of the Black History Month magazine, said the website was hacked deliberately (including a third time) to ensure that the content was not available or accessible in what is the most popular site in the UK on black history. The website is online throughout the year but interest peaks in October when it contains listings of thousands of commemorative events and a print magazine produced to mark the occasion uploaded on the website.

Black History Month or Black Diversity Month?

First signs of a subtle push back against increased assertion of black pride began emerging earlier in the year when a number of white dominated borough councils decided to scrap the name ‘Black History Month’ and rebrand it as ‘Black Diversity Month’ based on the spurious assertion of the promotion of ethnic inclusivity. But members of Britain’s black community see this as nothing more than a watering down of the celebration of black achievement. Maurice McLeod, one of only two black elected councillors of the London borough of Wandsworth, acknowledges that all cultures should be celebrated but asks pointedly “ why does this have to be at the expense of specifically black-focused celebrations?” McLeod continues, “we wouldn’t expect Chinese New Year to be rebranded as Asian New Year or change Gay Pride to ‘Everyone be Happy Day.” For Patrick Vernon, the ‘black diversity’ rebranding represents a colour blind approach by re-classifying Black History Month and creating a one size fits all multi-cultural history which often serves no real purpose for young people and the public.

Cultural Appropriation

Even more distasteful are the vulgar and insensitive acts of cultural appropriation. Several months ago, parents of children attending the St Winifride’s Catholic primary school in Newham East London were asked by the school to have their children attend school dressed as slaves in dirty worn-out clothes as part of a Black History Month celebration. As one parent remarked in disgust “You wouldn’t ask Jewish children to come in and re-enact the Holocaust.”

There is also the story of a school in the county of Kent which, in July, gave students a worksheet in which they were asked to imagine buying slaves at an auction as part of a history project. The year 8 students (12 year-olds av.) were asked to examine the characteristics of slaves listed as 16 lots and were told to choose the best slaves to suit their business with a budget of one hundred pounds (US$132 approx.). This report led Hehinde Andrews, an associate professor of sociology at Birmingham City University to comment:

“If this is how black history is taught in schools, then it is better they do not teach it at all. The levels of insensitivity just tell us how lightly the genocide of African people is viewed in the school system.”

Would a Labour Government Really Lead to a Change of Policy?

If Jeremy Corbyn leader of Britain’s Opposition party has his way and is to be taken at his word, a Labour government would improve the teaching of black history along with the history of the British empire, colonialism and slavery in schools. For Corbyn “ Black history is British history and it should not be confined to a single month each year.” He is quoted as saying: “In light of the Windrush scandal, Black History month has taken on a renewed significance and it is more important now than ever that we learn and understand as a society, the role and legacy of the British Empire colonization and slavery.” These are fine words and sentiments whilst in opposition but hardly bankable in light of past experiences. Corbyn and Labour should be held to their promise.

On the Continuing relevance of Black History Month

From their inception, the concept of commemorating black history in a limited period and in a specific month has had its critics both in the USA and in the UK. Opponents argue that you cant teach black history in the space of one month and that efforts should be concentrated on integrating it into the mainstream education system. In Britain, Corbyn has promised support for a new Emancipation Education Trust to educate future generations about slavery and the struggle for emancipation through school programmes, visits to historical sites and focusing on African civilizations before colonization. Patrick Vernon would add to that, budget support for black heritage organizations like the Black Cultural Archives and monuments like the proposed memorial 2007 recognizing the victims of the translantic trade in enslaved persons.

When Black History Month (BHM) was launched in 1987, everyone agreed that this was an important intervention following the riots in Brixton, Tottenham and Toxteth. It is difficult to assess the impact and legacy of the contribution of BHM over the last thirty-one years and whether the month has changed the perception of how people of African descent are viewed in society and within communities in exploring self-identity and racial pride.

In 2018, Britain is far from being a post-racial society with the issue of anti-semitism, the Windrush scandal, hate crimes against migrants and LGBT communities, surging numbers going through the mental health system and rising ‘stop and search’ against black people. This makes it even more critical that the importance of black history is advanced and promoted in the context of world history both past and present.

The question in 2018 therefore is what will the Black History Month of the future look like in the context of Brexit, changing demographics and intersectionality in black communities; and how will the growing debate over reparations and the argument that Afriphobia be recognized as a distinct form of racism against people of African descent, affect our narrative?

Jamaicaglobalonline acknowledges the contribution of Patrick Vernon OBE to the production of this article. An indefatigable campaigner for recognition of the Windrush Generation, he succeeded in having ‘Windrush Day’ officially declared in 2018 on the commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the docking of SS Windrush carrying the first immigrants from the Caribbean. Vernon’s efforts were recently recognized when he was named one of London’s most influential people in 2018 by the Evening Standard.