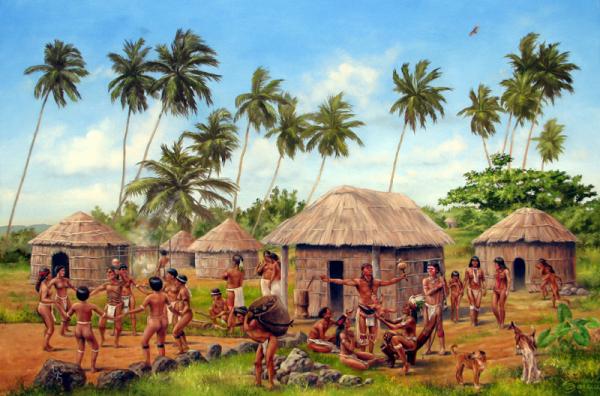

Crystal-clear, unpolluted waters, teeming with edible creatures. Lush, green vegetation. An abundance of fruits and berries. Herds of animals roaming the forests and the plains. Children running and laughing on sun-drenched beaches, frolicking in streams. Adults swinging in hammocks tied to silk cotton trees. And life was but a dream.

This is a glimpse back into the world of the Tainos on the island of Jamaica (Xaymaca or Yamaye or Yamayeka), land of woods and waters. They were a mostly fair-skinned people who had come over from the Central and South American mainlands. For centuries they existed in their own economic and social systems, which were sometimes upstaged by invasions from the more warlike Caribs.

Though they lived in villages of several hundred inhabitants, mainly near the sea or by the rivers, they also settled inland. Some lived in caves, others in huts made of wood and thatch palm fronds. They were spiritually connected to the environment, and had great reverence and respect for nature, the sky, moon, sun, stars, sea, land, and all their inherent features.

They regarded these elements as deities and personified them. Natural phenomena, hurricanes, storms, droughts, earthquakes, pestilence, etc were regarded the manifestations of these deities, who were represented by wood, stone and board sculptures called zemis or cemis, which were said to be inhabited by the deities and ancestral spirits (opias), which they believed roam the forests at night, indistinguishable from humans.

These deities were males and females, whom the Tainos included in every aspect of their life. They have different roles and were called upon for different reasons. Principal among the female deities was Attabeira or Atabey (Mother of all waters; Mother of the great one). There was also Guanbancex, ‘Lady of the winds’, ‘Mistress of hurricanes’. Among the males was Yucahu, the ‘Spirit of Yuca (cassava)’.

And in a world far removed from the European brand of Christianity they had their own perspectives of their origin, existence, and hereafter. In one of the stories, the god Locauna created man, who emerged from the caves and the earth. Eventually Locauna made the sun, moon and the fish in the sea.

To stay alive the farmers, fishermen, hunters and gathers nourished themselves with the food provided by the land and sea, and there was plenty of it. Cassava (yuca), potato (batata) and yam were staple crops. The cassava was used for a variety of purposes, including bammy. Tobacco, another staple, was used socially and ritualistically. Pepperpot was a common meal.

The role of women and men were clearly defined, men doing the hunting and the fishing, while the women kept house, including the weaving of cotton into cloth. Sea island cotton was exported to neighbouring islands to which they travelled in canoes (canoas) made from silk cotton trees (ceibas). Canoe Valley in south Manchester was so called because of the abundance of cotton trees in the area.

The social life of the Tainos was rich, replete with games, competitions and festivals. They hosted big celebrations called arietos, extravagant religious ceremonies for harvests, marriages, funerals, wars, etc. These celebrations sometimes lasted for days with the entire village participating.

The pomp and pageantry would take place on a ceremonial ground or court called batey, which was also the name of a popular ball (batu) game. They also made jewellery and working tools from wood, stones and shells, and created paintings on the walls of caves. Some of their rock sculptures (petroglyphs) are still well preserved.

However, in their idyllic settings, life was not a laissez-faire one. There were rules and protocols, familial, social and ceremonial. There was a rigid system of leadership and successions. The cacique (kasike) was at the helm of the leadership hierarchy in a chiefdom called cacicazgo. He lived in a rectangular house called caney and sat on a ceremonial stool called dujo (duho). Maximum respect was given to him, he who made sure that there was peace and order in cacicazgo.

The peaceful and idyllic life of the Tainos was disintegrated when the Europeans came to Jamaica in the last decade of the 15th century. Using superior weapon power the Europeans overwhelmed the ‘good and noble ones’, who, the history books say, did not put up much resistance. Murder, maiming, hard work and contagious European diseases killed the Tainos, and the history books also say that they all died.

But, it is also known that the Tainos, the first Maroons, who invented the barbecue style of cooking meat, interbred with the Africans who fled plantation servitude. So, while the great majority might have perished the narrative is that interbreeding has preserved their DNA, and there are people here in Jamaica who are making claim to their Taino ancestory and heritage.